Measurements of Success in Sports & Studies

You may have seen the new Netflix documentary ‘Beckham’, about one of England’s most well-known footballers. Near the start, Beckham talks about his school days

Mr. Ish is a 6th grade homeroom teacher at OYIS. He is a TCK, former international school student, and IB learner with over a dozen years of teaching experience in 7 countries.

“Where are you from?”

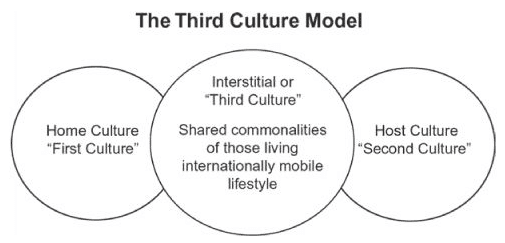

For many, the question bears no complication; after all, a stationary life is the norm for an overwhelming percent of the world’s population. But for the Third Culture Kid, this question is near-impossible to answer, providing a particularly interesting insight into the very mindset that makes them unique.

While all hopes of finding a definitive number have proven futile, the statistics I’ve amassed point to there being anywhere between 87 and 230 million people currently living voluntarily in a country different from their passport. Roughly 9% of those are students – students whose lives and worldviews have been irrevocably changed by their experiences. These are the people I’d like to focus on today. They go by many names: global nomads, transcultural children, cosmopolites, internationally mobile adolescents, cultural chameleons, and third culture kids among others.

If you are reading this as a member of the OYIS community, then chances are either you, your child, or someone close to you fits the bill. For the uninitiated, Third Culture Kids (TCKs for short) are individuals who have spent their formative years growing and adapting to a culture other than the one they were born into. It is a curious phenomenon wrought by an increasingly globalized world, coined originally by sociologist Dr. Ruth Useem and her husband John some 70 years ago.

The premise is simple: the experience abroad changes your brain. If this occurs during your formative years, then it will have lasting effects on your values, worldview, and ensuing lifestyle.

How do I know this, you may ask? Well, I happen to be a TCK myself. And while I am no longer a kid by any definition of the word, the effects from my experience abroad endure. Some 23 years ago my father took an assignment in Brazil, leaving me–a 6th grader at the time–to enter a whole new world rife with linguistic and cultural challenges, in addition to a novel kind of education–international education–at the American School of Rio de Janeiro. These crucial developmental years changed me as a person, leading me on an international path that I follow to this day.

It seems that I am not alone in experiencing powerful changes while living abroad. Studies of TCKs worldwide found shared personality traits and emotions transcendent of passport country, ethnicity, or language (Dewaele & Van Oudenhoven, 2009).

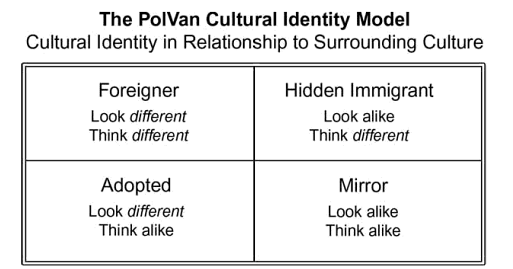

The most obvious one is confusion. TCKs struggle with self-identification and belonging because they identify with aspects of both their passport and host countries while failing to fit perfectly into either. To my Brazilian friends, I was clearly American – in dress, speech, and patterns of behavior – while to my Washingtonian friends, I was anomalous for the same reasons. In fact, after repatriating for high school, there were several classmates who just called me “Brazil Kid”, that is until I stopped emphasizing that side of my identity entirely. No one wants to stick out, kids especially. Just ask kikoku-shijo, hafu, and gyopo. It is this very notion that causes TCKs to shift their identity model with every plane they board, leading them to become quite adept chameleons in a variety of settings.

So while this does lead to feelings of cultural estrangement, it also strengthens TCK’s unique ability to relate to people of all cultures. Oftentimes TCKs are perceived as easy to get along with, likely due to our perpetual efforts practicing interpersonal and intercultural skills. This, at least anecdotally anyway, aligns with the many occasions in which people from different parts of the world said to me, “You’re really nice…for an American” or “You’re not like most Americans I’ve met.” A back-handed compliment for sure, but one I’ve heard enough to shrug right off and occasionally wear with pride.

The research appears to agree, as several studies into internationally mobile children show that TCKs score higher than non-TCKs in intercultural competency, empathy, multilingualism, and open-mindedness (Dewaele & Van Oudenhoven, 2009, Hoersting & Jenkins, 2011; Moore & Barker, 2012; Tannenbaum & Tseng, 2015). Perhaps this is why TCKs like myself feel most at home around diversity, be it in an international school, foreign setting, or multicultural social circle.

It should then come as no surprise that TCKs are considered internationally-minded. This terminology has become increasingly more valued in corporate circles due to globalization, leading education to follow suit. Among other international schools the world over, OYIS’s mission statement explicitly mentions the trait, “We are committed to empowering our students to become independent and globally-minded,” a sentiment the International Baccalaureate has touted for many years. In fact, when cross-referenced with the IB’s statements on international-mindedness, TCKs appear to be a natural fit, having developed these skills naturally simply as a result of living abroad.

While there are many advantages to the lifestyle, I should note it is not all sunshine and rainbows. TCKs face a plethora of challenges upon repatriation, transitioning into adulthood, and in the search for finding “home,” but when it comes to preparing your child for an increasingly globalized world where collaborative skills are considered on par with technical ones, TCKs have the advantage in social, emotional, and cultural intelligence.

Nowadays the research into TCKs has expanded to include those at different stages of life, often referred to as Third Culture Individuals (TCI) or Adult Third Culture Kids (ATCK), in addition to encompassing a broader range of cultural contexts. The more inviting terminology of the modern-day is deemed as Cross-Cultural Kids (CCK), which includes multicultural children, adoptees, refugees, and more. Regardless of the context, children in these circumstances face unique but shared challenges during a pivotal stage of their development, leading them to develop skills and strategies that can help them navigate the 21st-century landscape.

If you are interested in reading more, I suggest diving into Ruth Oseem’s website or Ruth Van Reken’s book Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds. You are also welcome to reach out with your questions to my school email, [email protected].

You may have seen the new Netflix documentary ‘Beckham’, about one of England’s most well-known footballers. Near the start, Beckham talks about his school days

Students who are eligible for Grades 10 or 11 in August 2023 are invited to take the 2022 Scholarship Exam. This exam is the first step to potentially receiving the OYIS Achievement Award.

Osaka YMCA International School is hosting a professional learning event on Saturday, February 8, 2025. The focus of the sessions will be Rethinking Assessments, broken

Since November 2022 when ChatGPT was released to the world, it’s seemed that AI has been everywhere in the news. Since then, AI has become

Celebrating Our Teachers: 5 Educators Earn SENIA Level 1 Certification! We are excited to announce that five of our dedicated teachers have recently completed their

Being Good Enough vs Being Perfect The idea of having to achieve the highest level of perfection is something that often affects the best of

Click here to start your application

Sign in Here

Osaka YMCA International School – Copyright 2025