Reese Ishmael

Fostering Independence in Children

In late March of 2022 Japan’s hit program 初めてのおつかい was elevated to the global stage, re-branded as Netflix’s Old Enough. The premise is simple: a toddler, typically between 2 and 4, goes out on their first errand by themselves, all while being filmed surreptitiously by a camera crew in disguise. Its premiere had a profound effect on the West, evidenced by a slew of articles in the first half of 2022 by such publications as TIME Magazine, The Guardian, and CNN. Even Saturday Night Live took a swing at the concept by spoofing an iteration about a ‘boyfriend’s first errand’.

Before long, the internet was set ablaze by the topic–and predictably, people’s reactions were divisive.

“Genuinely cried every single episode.” | “Will gladly watch 20 seasons of this!” |

“Maybe the US should consider designing places so that we don’t have to treat children up to the age of 16 like literal toddlers.” | |

“How is abandoning a tiny child to cross a busy road wholesome?” | “It’s all ‘fun’ and ‘interesting’ for us to watch but a child shouldn’t be ‘made’ to do this.” |

Source: Japan Today

Obviously Japan’s collectivist culture in addition to infrastructure, lack of crime, and many, many other variables factor into the creation and execution of Old Enough’s premise, but beyond the pinchable cheeks and puzzled expressions lie big questions: Are children capable of building independent behaviors? Is it even possible–let alone a good idea?

The answer, in my experience anyway, is a resounding yes–to all the above. The timing and structure of this independence matters, but all the same, it is possible. In my last few years teaching at Osaka YMCA International School I have witnessed the benefits first-hand of lengthening the lead, or at times, removing it completely. Let’s take a look into the theory and practice of it, in addition to investigating its benefits and difficulties in implementation.

The Age of Reason

To kick things off, it is important to establish that age matters. Children in Old Enough replicate praised behaviors such as a raised hand when crossing the road, or using polite language with members of the community, which for this age group is considered independent behavior. But independence that more closely resembles our own requires tough decision making, reflection, foresight, and a moral compass–all things that take time and maturity to develop.

Traditional education (Grade 1 upwards) starts at age seven for good reason: it marks the onset of what is referred to as the age of reason. According to psychotherapist Dr. Dana Dorfman, this is the “developmental cognitive, emotional, and moral stage in which children become more capable of rational thought, have internalized a conscience, and have better capacity to control impulses”. [5] Furthermore, Jean Piaget, whose theories kicked off the constructivist movement and developmental psychology, notes that at age seven children display a marked jump in their ability to think logically and use deductive reasoning, all while their egocentrism wanes. [6]

This is good news for those hoping to build independence. With a rudimentary understanding of morality, potential for empathy, and the capacity for rational thought, children from age 7 now possess the necessary foundations upon which to build long-lasting independent behaviors.

That being said, I wouldn’t send your child on a walkabout just yet. In order to meet their developmental needs, we need to construct an environment that can nurture these behaviors.

Environmental Supports for Agency

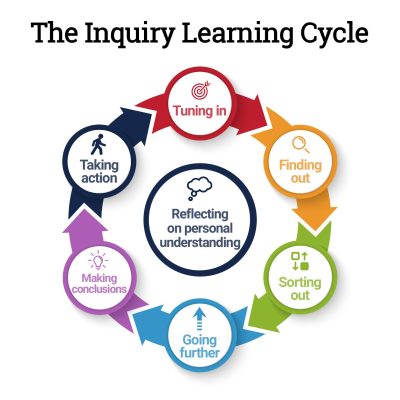

The International Baccalaureate was constructed with student agency in mind. Its inquiry process focuses on a student’s potential for discovery and action through quasi-structured activities and overarching thematic contexts.

In theory, this can lead to amazing student-led inquiries, projects, and events–which it does, but often with oversight and planning from the teacher. Then there is the Primary Years Program Exhibition (PYXP), a sizable undertaking which asks a student to plan, research, and present on a topic utilizing all the skills they have learned up to that point. Both these are beneficial and part of a bigger system that presents opportunities to gradually but safely guide students to independence, albeit in the classroom. [7] But what about everyday life? How can we foster independence in children when faced with situations outside of dedicated inquiry time?

1. Seeing Opportunity in Potential Disaster

In order to answer this question, allow me to pull from an educational context where inquiry is not the main focus. Not the most authentic everyday life scenario, I know, but bear with me. The situation is transferable.

In reading and writing classes at OYIS, we ascribe to what is known as the workshop model. In this, students listen to a mini-lesson then work on practicing what they have learned for an extended period of time. While this is taking place, the teacher will meet with individuals to have deeper conversations about their work and decide upon next steps that best target the child’s zone of proximal development.

Did you catch the potential disaster? Students are given independent production time while the teacher is engaged in conversation with a single student. That means that everybody else is surrounded by potential distractions and left to their own devices (literally for us in Grades 5 and 6) for over 30 minutes. What could go wrong?

Everything. Everything could go wrong. And yet therein lies the first step towards independence: an opportunity to practice it. Without giving children opportunities to exercise self-regulation, how can we ever expect them to prove themselves worthy?

2. De-stigmatizing and Normalizing Failure

If you are like me, you’ve already dreamed up a myriad of mistake-ridden multiverses where everything that can go wrong, does. Fortunately that is not the case, and if you were to step into my classroom for these workshops, you’d be pleasantly surprised by how sane a classroom it resembles.

Nevertheless, occasionally it happens. Children fail, and it is inevitable that they do. But it is also perfectly normal to do so, and failing marks their first step forward. I have spent far too much of my professional history trying to remove and mitigate obstacles, but with time I’ve come to learn that within these moments lies the greatest potential for learning. And by removing space for failure, I was robbing them of the chance to learn from their own experiences.

3. Regular Reflection with Coaching

Failure without accountability, though, is folly. Children are destined to enter a cycle of bad decisions unless they are made to reflect and learn from them. So while all those students are practicing time management, self-control, perseverance, and self-motivation, I meet with one. I meet to check in with them, on their progress, and to give advice. When children know they will need to answer for their progress, they are more apt to rise to the challenge.

Conferring also presents the added benefit of allowing children a chance to articulate their process and reflect. “What have you accomplished since our last meeting? What challenges have you encountered and how did you work through them?” These questions are an important part of the process. Sometimes just listening to them talk through their experience is all the help you need to support their independence. In more situations than not, these scenarios solidify an understanding faster than a barrage of teacher or parent reminders or advice.

Somewhere along the line though, children will hit a wall–a moment when they are at the edge of their patience or knowledge of how to overcome the challenge in front of them. That is when coaching is best utilized. Fostering independence means teaching kids how to help themselves, and some of those skills are new and need to be explained. Once they understand the foundations of independent problem-solving, all they need to do is practice it and see the successes that inevitably follow.

4. Recognition of Advancements

Acknowledging their progress is equally vital. Not all children know when they are on the right track, let alone consistently exhibit positive self-talk, so it is important we identify and celebrate their victories–especially when they overcame difficulty to get there.

Children often find themselves far removed from the systems that govern the world. Explanations can be curt (because I said so), shrouded in mystery (it’s complicated), or oversimplified (if you finish your milk, you’ll grow up big and strong). Being open and earnest about the process, when developmentally appropriate, can help children buy in.

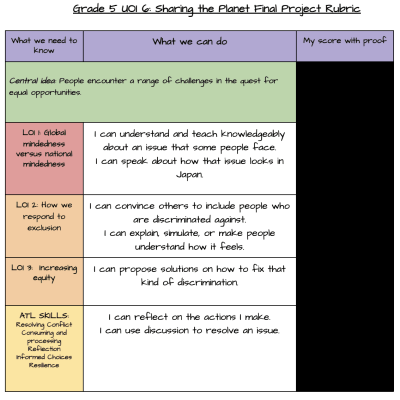

In my class, I share my planning documents and standards with students to do just this. I want them to see the system that dictates their day-to-day learning, not just for the sake of passive observation, but to make them active participants in the process. My time at OYIS has taught me that children ages 10 and up are perfectly capable of creating rubrics and assessing them against their own criteria, if structured at a developmentally-appropriate pace. Their reflections become so much richer and more authentic when they see the through-process. It doesn’t hurt that children love to be part of the decision-making, either, so if there is an opportunity to pull back the curtain, consider doing so.

6. Modeling

Last, and most importantly, is alignment. Children hate the fact that the world dictates two different sets of rules for children and adults. The old adage of “do as I say, but not as I do” does not fly in a society where inquiry and rationality are encouraged. As such, we must show we value these principles of healthy independent exploration to the same extent we hope they will.

There are many ways to show your devotion to the cause. My approach is to be open and honest about the process with students. It is not uncommon for me to pull from my own life experience in the classroom–and not just the rosy stuff, either. Children are morbidly curious and especially tuned in when I share my failures. And while I do not expect them to change based on my tales alone, I do think it helps them to understand we are all on our own journeys toward self-improvement.

Life is full of challenges, especially in our unique international context, so there is no excuse not to dive in. Whether it is cultural exchange, a long-term goal like learning a language, trying new foods / activities / endeavors, getting lost and finding your way back, or improving upon personal shortcomings–if you put yourself out there, kids are likely to take on a daunting task, especially if they can see how similar experiences have enriched your life.

Difficulties in Implementation

In the spirit of earnest exposition, I must admit these steps are easier to talk about than they are to implement. The cold hard truth of fostering independence is that it takes time and patience. Time to fail and patience not to intervene. Watching a child take 10 minutes to tie their shoe is sure to challenge your very relationship with time itself, but the experience may well save you and the child time in the long run. And that is why it is important to do so in the first place.

On a similar note, we as mentors set ourselves up for heartbreak when we spectate from the sidelines. Watching a child fail, struggle, or grow frustrated is no easy thing; such moments are thoroughly fleshed out in Old Enough, as parents are constantly fighting back tears of concern. But in the end, they are individuals on their own journey, and everything we do for them is one less chance for them to practice their independence.

A Final Note

A child’s life and daily cadence is considerably different outside of school compared to inside, so the scenarios and opportunities for fostering independence will likely present themselves differently, but I do believe that the methodology and steps for success align.

For families curious on how to further support their child’s independence, I have compiled some of the readings I explored while conducting research for this article. I hope you find it helpful, and by all means, if you find more or a success story to share, please do not hesitate to do so!

Resources:

Share this post

Measurements of Success in Sports & Studies

You may have seen the new Netflix documentary ‘Beckham’, about one of England’s most well-known footballers. Near the start, Beckham

Sign up for the OYIS Scholarship Exam

Students who are eligible for Grades 10 or 11 in August 2023 are invited to take the 2022 Scholarship Exam.

OYIS Alumni Chat Series: Sibling Stories

Home > Welcome to OYIS Alumni Chats, a new blog series where we catch up with our alumni and see

Making, Keeping, and Revitalizing Your New Year’s Resolutions

Home > With a new year comes a new burst of energy, new motivation, new changes, and New Year’s resolutions.

The Summer We Choose to Remember: Conquering Negativity Bias with Mindfulness

Home > As the summer break comes to an end, I have found myself unconsciously reflecting on how I spent

Professional Learning Event: Rethinking Assessment

Home > Osaka YMCA International School is hosting a professional learning event on Saturday, February 8, 2025. The focus of